'He revolutionised large parts of psychology'

Steven Pinker is a psychology professor at Harvard University. He is frequently named one of the world's top intellectuals and has twice been a finalist for the Pulitzer prize.

I've called Daniel Kahneman the world's most influential living psychologist and I believe that is true. He pretty much created the field of behavioural economics and has revolutionised large parts of cognitive psychology and social psychology. His central message could not be more important, namely, that human reason left to its own devices is apt to engage in a number of fallacies and systematic errors, so if we want to make better decisions in our personal lives and as a society, we ought to be aware of these biases and seek workarounds. That's a powerful and important discovery.

His work has had a great impact on my own. I've taught his research for more than 30 years and it's one of my favourite lectures when I teach psychology. My most recent book, The Better Angels of Our Nature, is about the historic decline of violence, a fact that I argue is underappreciated precisely because the human mind works the way Kahneman says it works, namely, that our sense of risk and danger is influenced by salient events that are available from memory. Our minds do not naturally process statistics on incidents of violence, and so Kahneman helps explain why my claim is news or why it's hard for people to believe.

In person, Daniel is very stimulating. When I first presented the material that became my book The Blank Slate, he gave me a comment that really sat with me: he noted that the idea of human nature with inherent flaws was consistent with a tragic view of the human condition and it's a part of being human that we have to live with that tragedy. It was a profound philosophical observation and it influenced my writing of that book.

We have our differences. I think he is a pessimist, whereas I am an optimist. I do think he's right that human nature saddles us with some unfortunate limitations, but I also think – and actually he himself shows in the "slow thinking" part of his book – that we have the means to overcome some of our limitations, through education, through institutions, through enlightenment. It will always be a flaw, human nature will always push back, but gradually, bit by bit, with two steps forward, one step back, I think that our better angels can push back against our limitations and flaws.

Thinking, Fast and Slow is an interesting capstone to his career, but his accomplishments were solidified well in advance of writing it and they'd be just as significant without the book. His work really is monumental in the history of thought.

'Danny is warm and moderate but also highly volatile'

Richard Thaler is a behavioural economist and expert in the psychology of decision-making. A professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, he is also the co-author of the bestseller Nudge, which explores how individuals and governments can influence people to make choices.

Although Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky [the cognitive psychologist who collaborated with Kahneman; he died in 1996] were not economists, they made behavioural economics possible. When I was a second-year assistant professor, I heard that they were going to be visiting the US from Israel and I made it my business to go to Stanford [University, where Kahneman used to work] that year to hang out with them. It changed my life. This was early in my career – I was 32 – and following the work of two psychologists was not a strategy that anyone thought was brilliant.

I spent enormous amounts of time with them at Stanford. There was a whole clan: Amos and his wife, Barbara, Danny and his now-wife, Anne Treisman, and Anne's soon-to-be-ex-husband – they all came to the Bay Area that year. My office was near Danny's and we spent countless hours wandering the hills, brainstorming about what the intersection of our two fields might be. They knew nothing about economics and I knew nothing about psychology, so it was one walk at a time, but we had a lot of fun.

Danny is warm and moderate but also, inside himself, highly volatile. He quit writing this book at least a dozen times. And I had to convince him not to quit, n+1 times. He genuinely didn't think anybody would buy it. It was a biased forecast – he prides himself on being a pessimist. He was shocked that it did so well and he's still in shock. He didn't think it would sell more than a million copies worldwide.

On every project we worked on together, there were several times when he would call me up, at 9.30 on a Saturday morning, to tell me that he'd figured out that what we were doing was crap – he'd found the fatal flaw. Amos, who was very even, used to provide a counterbalance. So after 1996, when Amos died, I took over the role of the one who would reassure him. I'd say: going on base rates, most of what you've done so far is not crap, therefore the probability that this is crap is low. I tried to speak his language, and, not knowing Hebrew, I thought I'd better go with the jargon.

Certainly his work has to be viewed as one of the most important accomplishments of 20th century science. It's hard to think of any psychologist whose work has influenced so many different fields.

'He made happiness respectable as a goal for society'

Professor Richard Layard is a British economist. After years researching inequality and unemployment, he became one of the first economists to study happiness, chairing the World Economic Forum's global agenda council on health and wellbeing at Davos in 2011 and co-editing a world happiness report in 2012 and 2013.

Danny Kahneman changed my life. He persuaded me that happiness is a real experience which can be measured and therefore studied and understood. I had always believed that the best society is one where there is the most happiness and (above all) the least misery. But the new science of happiness, which Danny was inspiring, made this ideal a hundred times more practicable.

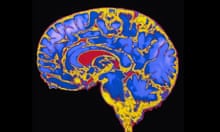

So I started writing a book on happiness, with Danny as my tutor. He invited me to Princeton. He introduced me to Richie Davidson, the great neuropsychologist who located areas of the brain where happiness and misery are experienced, and many other outstanding American psychologists. And, despite a dodgy back, he flew across the Atlantic four times to conferences we held, one of them on the draft of my book.

Danny is not only brilliant but exceptionally charming, which is how he became the focal point for people working on happiness. As Danny himself says, it is not often that you make close friends when you are beyond a certain age. I'm so lucky that it happened.

By chance I was visiting Princeton when, in 2002, Danny won the Nobel prize. That prize, more than anything, has made happiness respectable – not only as a subject of study but as a goal for society. In Britain, the government now measures happiness, the OECD promotes the standard international measurement of happiness and the UN holds a huge conference on happiness. And millions of people in their lives feel authorised to pursue meaningful objectives going way beyond material success.

And that is only part of the story. A huge part of Danny's work is on how we think – and how profoundly irrational we can be. That, too, is transforming business, however slowly, and explains the million copies he has sold of his new book. But, in the great sweep of history, I suspect he will be most remembered as the man who made happiness respectable.

'I learned one can force people to have a healthy outlook'

Risk engineering professor Nassim Nicholas Taleb is author of the bestselling book The Black Swan, about the problems created by rare events.

I met Daniel Kahneman in 2003, at a conference in Rome, soon after he got the Nobel Memorial prize. I was standing with a bunch of French researchers and this French-sounding fellow told me that he was puzzled by my idea that humans were not good at understanding rare events. It did not hit me that it was Kahneman, who it turned out, spoke French with no accent – not well-known since he avoids using it professionally and even socially.

I gave my talk to a crowd who took my lecture (on The Black Swan) with an icy cold – it was before the publication of the book and I was then totally unknown. I had informed the audience (financiers) about their cluelessness concerning rare events (black swans) and I could discern their annoyance – a few bankers looked a bit insulted. The chairman announced that there was going to be no Q&A. I feared that they would disinvite me from the rest of the conference, and perhaps even throw me out of the building, and if they could, the country. Kahneman was the next speaker. He unexpectedly saved my life when his opening sentence was that he "fully agreed with the previous speaker".

We became friends (in English). There have been memorable episodes, particularly a five-hour drive to rural Delaware, in which – among other problems – we were tailgated by a huge angry fellow, as, forgetting that Danny was in the car, I gave the man the finger.

People talk about his ideas in vague terms but I have been able to get from his work at least a dozen simple practical solutions.

When I met Danny, it was at a low point in my professional life, as I was starting to manage money for other people and, while I learned to administer my own psychology, thanks to trial and error and a dose of Stoic philosophy (Seneca), I proved incompetent at managing the clients' emotions. The clients had invested in a strategy expected to take steady, small losses for long periods against occasional large gains. They were convinced of its merits but they had difficulties with the emotional aspect of it – they rapidly forgot the properties of the strategy and became impatient. The mistake, it turned out, is that I presented the premium as a "loss", rather than an expense. There was no economic difference but, because of irrationality, there was a large behavioural one.

The first idea Danny gave me in Rome is that people do not perceive stand-alone objects, rather differences away from an anchor point. He said that it was not cultural: even the vision of babies was based on identifying variations. It was simply more economical for the brain to do so. Investors are more affected by changes in wealth than by wealth itself and they are very sensitive to the way information is presented to them; they are more unhappy if one tells them they have lost $10,000 (the variation) than if one informs them that their wealth is now $480,000 (the total). They just take a benchmark and react to variations from it. So one could make them react more rationally by modifying the anchor.

That small point was miraculous: upon my return to New York I forced the clients to write off the amount they were willing to lose during the year (like an insurance premium expensed at the beginning of the period). I then posted performance reports showing how much they "recovered", ie, money not lost. It was a wonder pill: clients became excited as they treated the money not lost as if it were a profit.

The second – equally potent – point I learned is that people do not aggregate information properly. When the portfolio is composed of many trades, and the net performance is positive, though some trades were up while a few were down, the clients got excited when they only saw the net total, but not when they saw the details. A small loss in a trade more than compensated by gains elsewhere would turn them off, and cause them to interrupt my lunch for an urgent conversation.

I also learned that one can change people's anchor to force them to have a realistic outlook on things. I am Lebanese and people keep bemoaning the relatively small tension in the wake of the Syrian civil war. But when I tell my mother to think of the turmoil that did not happen, her mood changes instantly.

'Ultimately he demonstrates that we are not rational'

Salley Vickers is a former psychotherapist and bestselling British author whose novels include Miss Garnet's Angel and Dancing Backwards.

Thinking, Fast and Slow confirmed for me that economics is not a science but deeply connected to our psyche. I know several grand economists and have been dismayed by their lofty disregard for how the human animal actually functions. Daniel Kahneman's lucid and witty accounts (backed by thorough research) of our apparently innate tendency to risk-aversion reveals the crucial link between economics and psychology.

It also underlines our problem with rationality. We are no less keen, it seems, on abandoning hopeless endeavours than we are at taking risks. Ultimately, Kahneman demonstrates, we are not rational creatures but instinctive ones and any attempt to make us act rationally must take that inbuilt bias into account or fail. As a psychoanalyst turned novelist, this was not news to me, but it is wonderful to have Kahneman's intellectual support for what I have always felt in my bones.

His other great gift to me is his insight that financial success has more to do with random chance than planning. The rise and fall of businesses has little to do with who runs them and much to do with a natural statistic – failure of any kind is usually, that is to say statistically, followed by success. On a more personal note, his dismissal of financial advisers and insurance policies, confirming my ignorant but it turns out accurate prejudice, made me rejoice that I never buy into these.

In short, Kahneman is a breath of fresh air and Thinking, Fast and Slow is a book I treasure.

Daniel Kahneman will be in conversation with David Baddiel on 18 March at Central Hall, Westminster at a 5x15 event partnered by the Observer. Sign up to be a Guardian Extra member and get reduced price tickets here

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion